(2 Kings 18:26; Ezra 4:7; Dan. 2:4), more correctly rendered 'Aramaic,' including both the Syriac and the Chaldee languages. In the New Testament there are several Syriac words, such as 'Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?' (Mark 15:34; Matthew 27:46 gives the Hebrews form, 'Eli, Eli'), 'Raca' (Matthew 5:22), 'Ephphatha' (Mark 7:34), 'Maran-atha' (1 Corinthians 16:22).

A Syriac version of the Old Testament, containing all the canonical books, along with some apocryphal books (called the Peshitto, i.e., simple translation, and not a paraphrase), was made early in the second century, and is therefore the first Christian translation of the Old Testament. It was made directly from the original, and not from the LXX. Version. The New Testament was also translated from Greek into Syriac about the same time. It is noticeable that this version does not contain the Second and Third Epistles of John, 2 Peter, Jude, and the Apocalypse. These were, however, translated subsequently and placed in the version. (see VERSION.)

“New Testament Languages and the Apocrypha” Primary N.T. Versions from Greek.Syriac-The Antioch church in Syria is where the disciples where first called Christians. Coptic - The Ethiopian eunuch from Acts 8 can be traced back to the Egyptian or Coptic church n.L -iat The Roman Catholic Church dominated for over 1900 years. A respected journal dedicated to studies of the Christian Apocrypha. Secret Scriptures Revealed. London: SPCK, 2013. E-mail Citation » A popular and new introduction to the Christian apocrypha. Suitable for newcomers to this area of study. Cartlidge, David R., and J. Art and Christian Apocrypha. London and New York.

1. (a.) Of or pertaining to Syria, or its language; as, the Syriac version Of the Pentateuch.2. (n.) The language of Syria; especially, the ancient language of that country.

SYRIAC VERSIONS' 1. Analogy of Latin Vulgate

2. The Designation 'Peshito' ('Peshitta')

3. Syriac Old Testament

4. Syriac New Testament

5. Old Syriac Texts

(1) Curetonian

(2) Tatian's Diatessaron

(3) Sinaitic Syriac

(4) Relation to Peshito

6. Probable Origin of Peshito

7. History of Peshito

8. Other Translations

(1) The Philoxenian

(2) The Harclean

(3) The Jerusalem Syriac

LITERATURE

As in the account of the Latin versions it was convenient to start from Jerome's Vulgate, so the Syriac versions may be usefully approached from the Peshitta, which is the Syriac Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.)

1. Analogy of Latin Vulgate:

Not that we have any such full and clear knowledge of the circumstances under which the Peshitta was produced and came into circulation. Whereas the authorship of the Latin Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) has never been in dispute, almost every assertion regarding the authorship of the Peshitta, and the time and place of its origin, is subject to question. The chief ground of analogy between the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) and the Peshitta is that both came into existence as the result of a revision. This, indeed, has been strenuously denied, but since Dr. Hort in his Introduction to Westcott and Hort's New Testament in the Original Greek, following Griesbach and Hug at the beginning of the last century, maintained this view, it has gained many adherents. So far as the Gospels and other New Testament books are concerned, there is evidence in favor of this view which has been added to by recent discoveries; and fresh investigation in the field of Syriac scholarship has raised it to a high degree of probability. The very designation. 'Peshito,' has given rise to dispute. It has been applied to the Syriac as the version in common use, and regarded as equivalent to the Greek (koine) and the Latin Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.)

2. The Designation 'Peshito' ('Peshitta'):

The word itself is a feminine form (peshiTetha'), meaning 'simple,' 'easy to be understood.' It seems to have been used to distinguish the version from others which are encumbered, with marks and signs in the nature of an apparatus criticus. However this may. be, the term as a designation of the version has not been found in any Syriac author earlier than the 9th or 10th century.

As regards the Old Testament, the antiquity of the Version is admitted on all hands. The tradition, however, that part of it was translated from Hebrew into Syriac for the benefit of Hiram in the days of Solomon is a myth. That a translation was made by a priest named Assa, or Ezra, whom the king of Assyria sent to Samaria, to instruct the Assyrian colonists mentioned in 2 Kings 17, is equally legendary. That the tr of the Old Testament and New Testament was made in connection with the visit of Thaddaeus to Abgar at Edessa belongs also to unreliable tradition. Mark has even been credited in ancient Syriac tradition with translating his own Gospel (written in Latin, according to this account) and the other books of the New Testament into Syriac

3. Syriac Old Testament:

But what Theodore of Mopsuestia says of the Old Testament is true of both: 'These Scriptures were translated into the tongue of the Syrians by someone indeed at some time, but who on earth this was has not been made known down to our day' (Nestle in HDB, IV, 645b). Professor Burkitt has made it probable that the translation of the Old Testament was the work of Jews, of whom there was a colony in Edessa about the commencement of the Christian era (Early Eastern Christianity, 71;). The older view was that the translators were Christians, and that the work was done late in the 1st century or early in the 2nd. The Old Testament known to the early Syrian church was substantially that of the Palestinian Jews. It contained the same number of books but it arranged them in a different order. First there was the Pentateuch, then Job, Joshua, Judgess, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Chronicles, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Ruth, Canticles, Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, Isaiah followed by the Twelve Minor Prophets, Jeremiah and Lamentations, Ezekiel, and lastly Daniel. Most of the apocryphal books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Book of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew and not from the Septuagint.

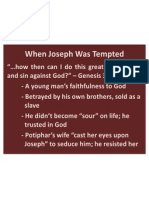

4. Syriac New Testament:

Of the New Testament, attempts at translation must have been made very early, and among the ancient versions of New Testament Scripture the Syriac in all likelihood is the earliest. It was at Antioch, the capital of Syria, that the disciples of Christ were first called Christians, and it seemed natural that the first translation of the Christian Scriptures should have been made there. The tendency of recent research, however, goes to show that Edessa, the literary capital, was more likely the place.

If we could accept the somewhat obscure statement of Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiastica, IV, xxii) that Hegesippus 'made some quotations from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac Gospel,' we should have a reference to a Syriac New Testament as early as 160-80 A.D., the time of that Hebrew Christian writer. One thing is certain, that the earliest New Testament of the Syriac church lacked not only the Antilegomena-2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation-but the whole of the Catholic Epistles and the Apocalypse. These were at a later date translated and received into the Syriac Canon of the New Testament, but the quotations of the early Syrian Fathers take no notice of these New Testament books.

From the 5th century, however, the Peshitta containing both Old Testament and New Testament has been used in its present form only as the national version of the Syriac Scriptures. The translation of the New Testament is careful, faithful and literal, and the simplicity, directness and transparency of the style are admired by all Syriac scholars and have earned for it the title of 'Queen of the versions.'

5. Old Syriac Texts:

It is in the Gospels, however, that the analogy between the Latin Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) and the Syriac Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) can be established by evidence. If the Peshitta is the result of a revision as the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) was, then we may expect to find Old Syriac texts answering to the Old Latin. Such texts have actually been found. Three such texts have been recovered, all showing divergences from the Peshitta, and believed by competent scholars to be anterior to it. These are, to take them in the order of their recovery in modern times, (1) the Curetonian Syriac, (2) the Syriac of Tatian's Diatessaron, and (3) the Sinaitic Syriac.

(1) Curetonian.

The Curetonian consists of fragments of the Gospels brought in 1842 from the Nitrian Desert in Egypt, and now in the British Museum. The fragments were examined by Canon Cureton of Westminster and edited by him in 1858. The manuscript from which the fragments have come appears to belong to the 5th century, but scholars believe the text itself to be as old as the 2nd century. In this recension the Gospel according to Matthew has the title Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, which will be explained in the next section.

(2) Tatian's 'Diatessaron.'

The Diatessaron of Tatian is the work which Eusebius ascribes to that heretic, calling it that 'combination and collection of the Gospels, I know not how, to which he gave the title Diatessaron.' It is the earliest harmony of the Four Gospels known to us. Its existence is amply attested in the church of Syria, but it had disappeared for centuries, and not a single copy of the Syriac work survives.

A commentary upon it by Ephraem the Syrian, surviving in an Armenian translation, was issued by the Mechitarist Fathers at Venice in 1836, and afterward translated into Latin. Since 1876 an Arabic translation of the Diatessaron itself has been discovered; and it has been ascertained that the Cod. Fuldensis of the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) represents the order and contents of the Diatessaron. A translation from the Arab can now be read in English in Dr. J. Hamlyn Hill's The Earliest Life of Christ Ever Compiled from the Four Gospels.

Although no copy of the Diatessaron has survived, the general features of Tatian's Syriac work can be gathered from these materials. It is still a matter of dispute whether Tatian composed his Harmony out of a Syriac version already made, or composed it first in Greek and then translated it into Syriac. But the existence and widespread use of a Harmony, combining in one all four Gospels, from such an early period (172 A.D.), enables us to understand the title Evangelion da-Mepharreshe It means 'the Gospel of the Separated,' and points to the existence of single Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, in a Syriac translation, in contradistinction to Tatian's Harmony. Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus in the 5th century, tells how he found more than 200 copies of the Diatessaron held in honor in his diocese and how he collected them, and put them out of the way, associated as they were with the name of a heretic, and substituted for them the Gospels of the four evangelists in their separate forms.

(3) Sinaitic Syriac.

In 1892 the discovery of the 3rd text, known, from the place where it was found, as the Sin Syriac, comprising the four Gospels nearly entire, heightened the interest in the subject and increased the available material. It is a palimpsest, and was found in the monastery of Catherine on Mt. Sinai by Mrs. Agnes S. Lewis and her sister Mrs. Margaret D. Gibson. The text has been carefully examined and many scholars regard it as representing the earliest translation into Syriac, and reaching back into the 2nd century. Like the Curetonian, it is an example of the Evangelion da-Mepharreshe as distinguished from the Harmony of Tatian.

(4) Relation to Peshito.

The discovery of these texts has raised many questions which it may require further discovery and further investigation to answer satisfactorily. It is natural to ask what is the relation of these three texts to the Peshitta. There are still scholars, foremost of whom is G. H. Gwil-liam, the learned editor of the Oxford Peshito (Tetraevangelium sanctum, Clarendon Press, 1901), who maintain the priority of the Peshitta and insist upon its claim to be the earliest monument of Syrian Christianity. But the progress of investigation into Syriac Christian literature points distinctly the other way. From an exhaustive study of the quotations in the earliest Syriac Fathers, and, in particular, of the works of Ephraem Syrus, Professor Burkitt concludes that the Peshitta did not exist in the 4th century. He finds that Ephraem used the Diatessaron in the main as the source of his quotation, although 'his voluminous writings contain some clear indications that he was aware of the existence of the separate Gospels, and he seems occasionally to have quoted from them (Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, 186). Such quotations as are found in other extant remains of Syriac literature before the 5th century bear a greater resemblance to the readings of the Curetonian and the Sinaitic than to the readings of the Peshitta. Internal and external evidence alike point to the later and revised character of the Peshitta

6. Probable Origin of Peshito:

How and where and by whom was the revision carried out? Dr. Hort, as we have seen, believed that the 'revised' character of the Syriac Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) was a matter of certainty, and Dr. Westcott and he connected the authoritative revision which resulted in the Peshitta with their own theory, now widely adopted by textual critics, of a revision of the Greek text made at Antioch in the latter part of the 3rd century, or early in the 4th. The recent investigations of Professor Burkitt and other scholars have made it probable that the Peshitta was the work of Rabbula, bishop of Edessa, at the beginning of the 5th century. Of this revision, as of the revision which plays such an important part in the textual theory of Westcott and Hort, direct evidence is very scanty, in the former case altogether wanting. Dr. Burkitt, however, is able to quote words of Rabbula's biographer to the effect that 'by the wisdom of God that was in him he translated the New Testament from Greek into Syriac because of its variations, exactly as it was.' This may well be an account of the first publication of the Syriac Vulg, the Old Syriac texts then available having been brought by this revision into greater conformity with the Greek text current at Antioch in the beginning of the 5th century. And Rabbula was not content with the publication of his revision; he gave orders to the priests and the deacons to see that 'in all the churches a copy of the Evangelion da-Mepharreshe shall be kept and read' (ib 161;, 177). It is very remarkable that before the time of Rabbula, who ruled over the Syr-speaking churches from 411 to 435, there is no trace of the Peshitta, and that after his time there is scarcely a vestige of any other text. He very likely acted in the manner of Theodoret somewhat later, pushing the newly made revision, which we have reason to suppose the Peshitta to have been, into prominence, and making short work of other texts, of which only the Curetonian and the Sinaitic are known to have survived to modern times.

7. History of Peshito:

The Peshitta had from the 5th century onward a wide circulation in the East, and was accepted and honored by all the numerous sects of the greatly divided Syriac Christianity. It had a great missionary influence, and the Armenian and Georgian VSS, as well as the Arabic and the Persian, owe not a little to the Syriac. The famous Nestorian tablet of Sing-an-fu witnesses to the presence of the Syriac Scriptures in the heart of China in the 7th century. It was first brought to the West by Moses of Mindin, a noted Syrian ecclesiastic, who sought a patron for the work of printing it in vain in Rome and Venice, but found one in the Imperial Chancellor at Vienna in 1555-Albert Widmanstadt. He undertook the printing of the New Testament, and the emperor bore the cost of the special types which had to be cast for its issue in Syriac. Immanuel Tremellius, the converted Jew whose scholarship was so valuable to the English reformers and divines, made use of it, and in 1569 issued a Syriac New Testament in Hebrew letters. In 1645 the editio princeps of the Old Testament was prepared by Gabriel Sionita for the Paris Polyglot, and in 1657 the whole Peshitta found a place in Walton s London Polyglot. For long the best edition of the Peshitta was that of John Leusden and Karl Schaaf, and it is still quoted under the symbol Syriac schaaf, or Syriac Sch. The critical edition of the Gospels recently issued by Mr. G. H. Gwilliam at the Clarendon Press is based upon some 50 manuscripts. Considering the revival of Syriac scholarship, and the large company of workers engaged in this field, we may expect further contributions of a similar character to a new and complete critical edition of the Peshitta

8. Other Translations:

(1) The Philoxenian.

Besides the Peshitta there are other translations which may briefly be mentioned. One of these is the Philoxenian, made by Philoxenus, bishop of Mabug (485-519) on the Euphrates, from the Greek, with the help of his Chorepiscopus Polycarp. The Psalms and portions of Isaiah are also found in this version; and it is interesting as having contained the Antilegomena-2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude.

(2) The Harclean.

Another is the Harclean, which is a revision of the Philoxenian, undertaken by Thomas of Harkel in Mesopotamia, and carried out by him at Alexandria about 616, with the help of Greek manuscripts exhibiting western reading. The Old Testament was undertaken at the same time by Paul of Tella. The New Testament contains the whole of the books, except Rev. It is very literal in its renderings, and is supplied with an elaborate system of asterisks and daggers to indicate the variants found in the manuscripts.

(3) The Jerusalem Syriac.

Mention may also be made of a Syriac version of the New Testament known as the Jerusalem or Palestinian Syriac, believed to be independent, and not derived genealogically from those already mentioned. It exists in a Lectionary of the Gospels in the Vatican, but two fresh manuscripts of the Lectionary have been found on Mt. Sinai by Dr. Rendel Harris and Mrs. Lewis, with fragments of Acts and the Pauline Epistles. The dialect employed deviates considerably from the ordinary Syriac, and the Greek text underlying it has many peculiarities. It alone of Syriac manuscripts has the pericope adulterae. In Matthew 27:17 the robber is called Jesus Barabbas. Gregory describes 10 manuscripts (Textkritik, 523).

LITERATURE.

Nestle, Syrische Uebersetzungen, PRE3, Syriac VSS, HDB, and Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the Greek New Testament, 95-106; G. H. Gwilliam, Studia Biblica, II, 1890, III, 1891, V, 1903, and Tetraevangelium sanctum Syriacum; Scrivener, Intro4, 6-40; Burkitt, 'Early Eastern Christianity,' Texts and Studies, VII, 2:1-91, Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, I, II, and 'Syr VSS,' EB; Gregory, Textkritik, 479-528.

T. Nicol

762. Aramith -- the language of Aram (Syria)

762. Aramith -- the language of Aram (Syria)... in the Syrian language, in Syriac. Feminine of 'Arammiy; (only adverbial)in Aramean --

in the Syrian language (tongue), in Syriac. see HEBREW 'Arammiy. ...

/hebrew/762.htm

Syriac And Armenian Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures King James Version

- 6kSyriac Calendar.

... Memoirs of Edessa. And Other Ancient Syriac Documents. [Translated by the Rev.

BP Pratten, BA] Syriac Calendar. A Note by the Translator ...

//christianbookshelf.org/unknown/the decretals/syriac calendar.htm

Introduction to Ancient Syriac Documents.

... Ancient Syriac Documents. Moses of Chorene. History of Armenia.

Introduction to Ancient Syriac Documents. 1. The preceding ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/introduction to ancient syriac documents.htm

Introductory Note to the Syriac Version of the Ignatian Epistles

...Syriac Version Introductory Note to the Syriac Version of the Ignatian

Epistles. When the Syriac version of the Ignatian Epistles ...

/.../introductory note to the syriac.htm

Commendation and Exhortation. Syriac Version

...Syriac Version Chapter I.'Commendation and exhortation. Syriac Version.

Because thy mind is acceptable to me, inasmuch as it is ...

/.../chapter i commendation and exhortation syriac.htm

Ancient Syriac Documents Relating to the Earliest Establishment of ...

... Memoirs of Edessa. And Other Ancient Syriac Documents. ... soterian: and so the Syriac

word, meaning 'life,' is generally to be translated in this collection.--Tr. ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents relating to.htm

Ambrose.

... Ancient Syriac Documents. Moses of Chorene. History of Armenia. Ancient

Syriac Documents. Ambrose. A memorial [3496] a which ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents ambrose.htm

Bardesan.

... Ancient Syriac Documents. Moses of Chorene. History of Armenia. Ancient Syriac

Documents. Bardesan. The Book of the Laws of Divers Countries. [3356] ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents bardesan.htm

The Teaching of the Apostles.

... Memoirs of Edessa. And Other Ancient Syriac Documents. [Translated by the Rev. BP

Pratten, BA] Ancient Syriac Documents. The Teaching of the Apostles. ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents the teaching 2.htm

The Teaching of Add??us the Apostle.

... Memoirs of Edessa. And Other Ancient Syriac Documents. [Translated by the Rev. BP

Pratten, BA] Ancient Syriac Documents. The Teaching of Add??us the Apostle. ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents the teaching.htm

A Canticle of Mar Jacob the Teacher on Edessa.

... Memoirs of Edessa. And Other Ancient Syriac Documents. [Translated by the

Rev. BP Pratten, BA] Ancient Syriac Documents. A Canticle ...

/.../unknown/the decretals/ancient syriac documents a canticle.htm

... Easton's Bible Dictionary (2 Kings 18:26; Ezra 4:7; Dan. 2:4), more correctly rendered

'Aramaic,' including both the Syriac and the Chaldee languages. ...

/s/syriac.htm - 26k

Armenian

... AD; died 332), but, as Armenian had not been reduced to writing, the Scriptures

used to be read in some places in Greek, in others in Syriac, and translated ...

/a/armenian.htm - 18k

Apostles (79 Occurrences)

... later Uncials like Codex Modena, Codex Regius, Codex the Priestly Code (P), the

Cursives, the Vulgate, the Peshitta and the Harclean Syriac and quotations from ...

/a/apostles.htm - 62k

Jeremy (2 Occurrences)

... March, Chisl, in the Syriac Hexateuch), it follows Lamentations as an independent

piece, closing the supposed writings of Jeremiah. ... (2) The Syriac. ...

/j/jeremy.htm - 12k

Thaddaeus (2 Occurrences)

... (4) The Abgar legend, dealing with a supposed correspondence between Abgar, king

of Syria, and Christ, states in its Syriac form, as translated by Eusebius ...

/t/thaddaeus.htm - 11k

Shinar (8 Occurrences)

... shi'-nar (shin`ar; Senaar Sen(n)aar): 1. Identification 2. Possible Babylonian Form

of the Name 3. Sumerian and Other Equivalents 4. The Syriac Sen'ar 5. The ...

/s/shinar.htm - 27k

Syrian (12 Occurrences)

... Noah Webster's Dictionary 1. (a.) Of or pertaining to Syria; Syriac. 2. (n.) A native

of Syria. ... SYRIAN; LANGUAGE. sir'-i-an (the King James Version SYRIAC). ...

/s/syrian.htm - 10k

Aramaic (12 Occurrences)

... literature of Syria and Mesopotamia; Aramaean; -- specifically applied to the northern

branch of the Semitic family of languages, including Syriac and Chaldee. ...

/a/aramaic.htm - 31k

Susanna (1 Occurrence)

... I. In the Harklensian Syriac (Ball's W2) its title is 'The Book of Little (or the

child?) Daniel.' 2. Canonicity and Position: Susanna was with the other ...

/s/susanna.htm - 17k

Arabic

... in those circles it is not surprising that most of such material, and indeed of

the entire literary output, consists of translations from Syriac, Greek or ...

/a/arabic.htm - 17k

What is the Diatessaron? | GotQuestions.org

What is the Letter of King Abgar to Jesus? | GotQuestions.org

Syriac: Dictionary and Thesaurus | Clyx.com

Bible Concordance • Bible Dictionary • Bible Encyclopedia • Topical Bible • Bible Thesuarus

The Syriac text of IGT (Syr) is found in several interrelated compilations of Lives of Mary:

1. The earliest of these lives is extant in two manuscripts which compile the Protevangelium of James, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and the Assumption of the Virgin. The first publication of the IGT material from one of these manuscripts (London, British Library, Add. 14484 of the sixth century) came in 1865 by William Wright (Contributions to the Apocryphal Literature of the New Testament. London: Williams & Norgate, 1865, pp. 11-16 [text], 6-11 [translation]). The second manuscript (Göttingen, Universitätsbibliothek, Syr. 10 of the fifth or sixth century) was collated against Wright’s manuscript by W. Baars and J. Heldermann (“Neue Materielen zum Text und zur Interpretation des Kindheitsevangeliums des Pseudo-Thomas.” Oriens Christianus 77 [1993]: 191-226; 78 [1994]: 1-32). A third witness of this type is found in Vatican, Syr. 159 (dated 1622/1623), which I presented in a diplomatic edition in “The Infancy Gospel of Thomas from an Unpublished Syriac Manuscript. Introduction, Text, Translation, and Notes,” Hugoye: Journal for Syriac Studies16.2 (2013):225–99. IGT is here appended to (but not incorporated into) the Arabic Infancy Gospel in Garshuni. My critical edition (The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition. Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies 48. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2017) includes features all three of these manuscripts with two very similar to the Vatican manuscript and one additional witness with a text similar to the fifth/sixth-century manuscripts.

2. The West Syriac Life of Mary: this compilation features the Protevangelium of James, the Vision of Theophilus, IGT, and the 6 Books Dormition of the Virgin. Some manuscripts of this type, and of the East Syriac History of the Virgin (see below), are listed by Anton Baumstark (Geschichte der syrischen Literatur mit Ausschluss der christlich-palästinensischen Texte. Bonn: A. Marcus & E. Webers Verlag, 1922, p. 69 n. 12 and 99 n. 4) and by S. C. Mimouni (“Les Vies de la Vierge; État de la question,” Apocrypha 5 [1994]: 239-243). These and a number of additional manuscripts are described inThe Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition). The West Syriac Life of Mary is extant also in Garshuni.

3. The East Syriac History of the Virgin: this compilation includes the Protevangelium of James, material incorporated also in the Arabic Infancy Gospel, IGT, episodes from the canonical gospels, the Assumption of the Virgin, and other miracles. The entire text was published from two manuscripts by E. A. Wallis Budge in 1899, though the IGT material was extant in only one of the manuscripts (a personal copy commissioned by Budge but based on a 13/14th century original). Three additional Hist. Vir. manuscripts also contain the IGT material. A new critical edition of this portion of the text is featured in The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition.

The Syriac tradition also spawned several offspring: the aforementioned Arabic Infancy Gospel, the Armenian Infancy Gospel (both likely related to Hist. Vir.), the Georgian version of IGT, and a rarely-discussed Arabic version of IGT (published in a new edition by Slavomír ?éplö based on two manuscripts in The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition, pp. 229-43.

The translation of the Syriac Inf. Gos. Thom. given below is excerpted from “The Infancy Gospel of Thomas (Syriac)” (New Testament Apocrypha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Edited by Tony Burke and Brent Landau. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2016, pp. 52–68). It is based on the four of the five principal manuscripts of the independently-transmitted text of the gospel (the fifth, though used in The Infancy Gospel of Thomas in the Syriac Tradition, had not yet been noted). The West Syriac and East Syriac compilations are employed when required to adjudicate between readings in the other manuscripts. Chapter and verse divisions follow the standard numbering of Tischendorf’s Greek A text except chapter six which is significantly longer in the Syriac and other versions.

____________

The Childhood of Our Lord Jesus

2 1Now when the boy Jesus Christ was five years old, he was playing at the ford of streams of water. And he was catching and confining the waters and directing them in channels and making them enter into pools. He was making the waters become pure and bright. 2He took soft clay from the wet ground and molded twelve birds. It was the Sabbath and many children were with him.

3But one of the Jews saw him with the children making these things. He went to his father Joseph and incited him against Jesus, and said to him, “On the Sabbath he molded clay and fashioned birds, something that is not lawful on the Sabbath.”

4Joseph came and rebuked him, and said to him, “Why are you making these things on the Sabbath?” Then Jesus clapped his hands and made the birds fly away before these things that he said. And he said, “Go, fly, and be mindful of me, living ones.” And these birds went away, twittering. 5But when that Pharisee saw (this) he was amazed and went and told his friends.

31The son of Hann?n the scribe also was with Jesus. He took a willow branch and leaked out and broke down the pools and let the waters escape that Jesus had gathered together, and dried up their pools.2When he saw what had happened, Jesus said to him, “Without root shall be your shoot and your fruit shall dry up like a branch that is broken by the wind and is no more.” 3Suddenly, that boy withered.

4 1Again Jesus was going with his father, and a boy (was) running and struck him on the shoulder. Jesus said to him, “You shall not go on your way.” And suddenly he fell down and died. Those who saw him cried out and said, “From where was this boy born, that all his words are a deed?” 2The family of that boy who died approached Joseph his father and were blaming him and saying to him, “As long as you have this boy you cannot dwell with us in the village, unless you teach him to bless.”

5 1Joseph approached the boy and was lecturing him and saying to him, “Why do you do these things? For what reason do you say these things? These (people) suffer and hate us.” Jesus said, “If the words of my Father were not wise, he would not know (how) to instruct children.” He spoke again, “If these were children of the bedchamber, they would not be receiving a curse. These shall not see their torment.” At that moment, those who were accusing him were blinded.

2Joseph became angry and seized (him) by his ear and pulled it hard.

3Jesus answered and said to him, “It is enough for you, that you should be seeking me and finding me; for you have acted ignorantly.”

6 1A teacher, whose name was Zacchaeus, heard him speaking with his father and said, “O wicked boy!” 2He said to Joseph, “How long will you not wish to hand over this boy, so that he may learn to love children his age and honor old age and to be in awe of elders, in order that the love of children may be with him and, moreover, so that he may teach them?” 2aJoseph said, “Who is able to teach a boy like this? Do you not think that he deserves a small cross?”

2bJesus answered and said to him, “Teacher, these words that you have now spoken and these names that you name, I am a stranger to them; for I am outside of you, yet I dwell among you. Honor of the flesh I have not. You (live) by the law and by the law you remain. For when you were born, I was. But you think that you are my father. You shall learn from me that teaching that no one else knows nor is able to teach. As for that cross you mentioned, the one to whom it belongs shall bear it. For when I am greatly exalted I shall lay aside what is mixed in your race. For you do not know where I was born nor where you are from; for I alone know you truly—when you were born and how much time you have to remain here.”

2cWhen they heard, they were amazed and cried out greatly and said, “O wonderful sight and sound! Words like these we have never heard anyone speak—neither the priests, nor the scribes, nor the Pharisees. Where was this one born, who is five years old and speaks such words? Such a one has never been seen among us.” 2dJesus answered and said to them, “You wonder about me and you do not believe me concerning what I have said to you. I said that I know when you were born; and I have even more to say to you.”

2eWhen they heard (these words), they were silent and unable to speak. He approached them again and said, laughing, “I laughed at you because you marvel at trifles and you are becoming small in your mind.”

2fWhen they were comforted a little, Zacchaeus the teacher said to the father of Jesus, “Bring him to me and I will teach him what is proper for him to learn.” He coaxed him and made him go into the school. Yet, going in, he was silent. But Zacchaeus the scribe was beginning to teach him (starting) from Aleph, and repeating to him many times the whole alphabet. He said to him that he should answer and speak after him, but he was silent. Then the scribe was angry and struck him with his hand upon his head. And Jesus said, “The smith’s anvil, when struck repeatedly, may be instructed, yet is unfeeling. I can say those things spoken by you like a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. These do not reply with any sound nor do they have the power of knowledge and understanding.”

3Then Jesus said all the letters from Aleph to Tau with much wisdom. He answered again and said, “Those who do not know the Aleph, how do they teach the Beth? Hypocrites! Teach what is the Aleph and then I will believe you concerning the Beth.” 4Then Jesus began to inquire concerning the form of each character. He began with the letters. Concerning the first, why it has many angles and characters, pointed, thick and prostrate and projected and extended; their summits gathered together and sharp and ornamented and erect and squared and inverted; and transformed and folded over and bent at their sides, and fixed in a triangle and crowned and clothed in life.

7 1Then Zacchaeus the scribe, amazed and astonished on account of all these names and the greatness of his speech, cried out and said, “I have brought this <matter> on myself. 2Take him away from me, I beg of you. It is not right for this one to be this (way) on the Earth; truly this one is worthy of a great cross. He is able to even set fire to fire. And I think that this one was born before the flood of Noah. What womb carried this one? Or what mother reared this one? For I cannot bear this one. I am in a great stupor because of him; and I am out of my mind. Wretched am I to think I had acquired a student; and, although I considered him a student, he was my teacher.

3“O my friends! I cannot bear it. I am fleeing from the village; I cannot look upon him. By a little child I, an old man, am defeated. But what can I, who was defeated, say? How, even from the beginning, I did not understand a thing this one was saying. Have mercy on me! I am dying. My soul is clearly before my eyes because of the order of his voice and the beauty of his words. 4This one is something great—either a god, or an angel, or what I should say I do not know.”

8 1Then the boy Jesus laughed and said, “Let those in whom there is no fruit, produce fruit; and let the blind see the living fruit of judgment.” 2Those who had fallen under his curse came alive and rose up. No one was daring to anger him again.

9 1One time, on the day of the Sabbath, Jesus was playing with children on a roof. One of the children fell and died. When those other children saw (what had happened), they ran away, and Jesus remained alone. 2The family of the one who was dead seized him and said to him, “You threw the boy down.” And Jesus said, “I did not throw him down.” They were accusing him.

3Then he came down to the dead one and said in a loud voice, “Zeno, Zeno”—for thus indeed was his name—“did I throw you down?” Immediately, he leaped up and stood and said to him, “No, my Lord.” 4All of them were amazed. Even the boy’s parents were praising God for this wonder that had happened.

11 1Again, when Jesus was seven years old, his mother sent him to fill water. And in the press of a great crowd, his pitcher struck (against something) and was broken. 2Then Jesus spread out the cloak with which he was covered and he collected and brought (home) that water. His mother Mary was astonished and she was keeping in her heart all that she was seeing.

12 1Once again Jesus was playing. He sowed one measure of wheat. 2And he harvested 100 cors and gave them to the people of the village.

13 1Jesus was eight years old. Joseph was a carpenter and made nothing else but ploughs and yokes. A man had ordered from him a bed of six cubits. One plank did not have the (proper) length on one side, for it was shorter than the other. The boy Jesus said to his father, “Take hold of the end of the one shorter than the other.” 2Jesus took the length of the wood and pulled and stretched it and made it equal to its other. Jesus said to Joseph his father, “Do henceforth what you wish.”

Syriac And Armenian Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Bible

141When Joseph saw his intelligence, he wished to teach him writing, and he brought him to the school. The scribe said to him, “Say Aleph.” And Jesus said <it>. Again the scribe added that he should say Beth. 2Jesus said to him, “Tell me first what Aleph is, and then I will tell you about Beth.” The scribe was furious and struck him, and immediately (the scribe) fell down and died.

3Jesus went back to his family. Joseph called Mary his mother and spoke to her and commanded her not to permit him to go out of the house, so that those who strike him will not die.

15 1But another scribe said to Joseph, “Hand him over to me. I will teach him by flattery.” 2Jesus entered the school. He took a scroll and was reading, not what was written, but he opened his mouth and spoke in the spirit, so that that scribe sat with him on the ground and beseeched him. Great crowds, hearing his words, assembled and stood there. Jesus thus opened his mouth and was speaking, so that all who arrived and stood there might be amazed and astonished.

3When Joseph heard, he ran <and> came because he was afraid lest the scribe also would die. The scribe said to Joseph, “You have delivered to me not a student but a master.” 4And Joseph took him and led him back to his home.

16 1Again Joseph had sent his son James to gather sticks. Jesus was going with him. While they were gathering sticks, a deadly viper bit James on his hand. 2When Jesus came near to him, he did to him nothing more than stretch out his hand and blow on the bite. And it was healed, the viper died, and James lived.

19 1 When Jesus was twelve years old, they had gone to Jerusalem, as it was custom for Joseph and Mary to go to the festival of Passover. When they had made Passover, they returned to their home. When they had turned to come <home>, Jesus remained in Jerusalem. Neither Joseph nor Mary his mother knew <it>, but they thought that he was with their companions.

2When they came to the rendezvous of that day, they were seeking him among their kinsfolk and among those whom he knew. When they did not find Jesus, they returned to Jerusalem and were seeking him. After three days they found him in the temple, sitting among the teachers, and listening to them and questioning them. All those hearing were astonished at him, because he was silencing those teachers, for he was expounding to them the parables of the prophets and the mysteries and allegories of the law.

3His mother said to him, “My son, why have you done this to us so? We were distressed and anxious and searching for you. Jesus answered and said, “Why were you searching for me? Do you not know that it is fitting for me to be in my Father’s house?” 4The scribes and the Pharisees answered and said to Mary, “Are you the mother of this boy? The Lord has blessed you in your fruit, for the glory of wisdom such as this in children we have neither seen nor heard that anyone has spoken.

5He rose and went with them and was obedient to his parents. But his mother was preserving all these words in her heart. Jesus was excelling and growing in wisdom and stature and grace before God and before men.

Syriac And Armenian Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Study

<Here> ends the Childhood of our Lord Jesus.